I was 13 when I had my first sexual experience with another guy. A few days later, I caught a cold. The symptoms were ordinary—a few coughs, a runny nose—but that didn’t stop me from working myself into a panic. I was convinced I had contracted HIV/AIDS, and would soon be dead.

I was born in 1987, three days before Larry Kramer founded the influential advocacy group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) in reaction to the nearly 50,000 reported deaths at the hands of government foot-dragging and political neglect. Thirteen years later, there wasn’t a single mention of the virus in my Hawaii middle school’s sex education program. It took a frantic search on my computer’s lagging dial-up connection to learn that my chance of contracting HIV through oral sex was .04 percent.

According to Planned Parenthood’s most recent poll, 93 percent of parents support sex education being taught in middle school. Less agreed upon is how.

Despite evidence that abstinence-only sex education is not effective at preventing teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, 27 states still require that abstinence be stressed in sex education. According to the Guttmacher Institute, only 13 states require sex and HIV education be medically accurate, with only 34 (plus the District of Columbia) mandating HIV education. Last April, the Trump administration announced that it would favor funding programs that emphasized “sexual risk avoidance”—political gobbledegook for “abstinence.”

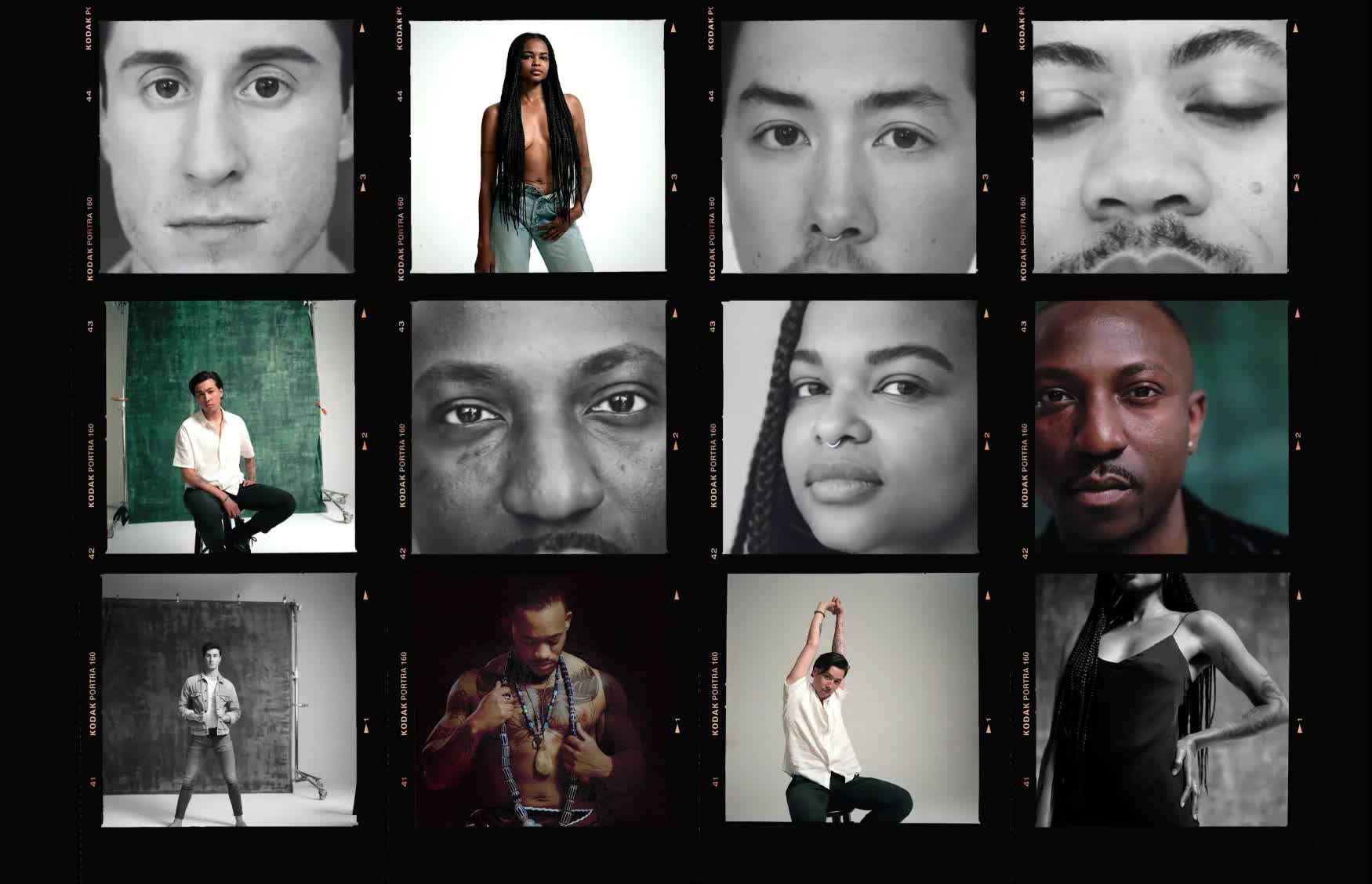

I spoke to five people—who also grew up shortly after the onset of the AIDS epidemic—about how sex education (or lack thereof) impacted their sexual identities, their relationship to consent, and their understanding of HIV/AIDS and other STIs.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Even though I went to a public middle school in Portland, Oregon, which people think of as being so liberal, we had abstinence-based sex ed. They hired an outside organization called the STARS Program [Students Today Aren’t Ready for Sex]. They were just like: “Here are all of the horrible things that can happen to you if you have sex, so don’t do it. And that was it.”

There was no room for conversations about gender, consent, or sexuality, which at the time—those are prime years when queer and trans kids are figuring out what’s going on. The assumption of heterosexuality caused me to tune out, because I thought: Well, none of this applies to me.

As a result, I didn’t learn much about sexual health and education and stuff like that until I was older and became a sexual assault advocate.

I remember some of my classmates asking really basic questions about what was happening with their bodies and the instructors were just like, “Well, you don’t need to worry about that.” It made everyone even more confused than they were before, because suddenly it was bad to talk about it.

I think the only thing I was taught about HIV is that it’s contracted through sex with two men. I didn’t know the difference between HIV and AIDS until I was well into adulthood.

There was a lack of education around consent. My friends who had been sexually assaulted were trying to talk about it, but didn’t have the language to express what had happened to them. Growing up as a girl, we were talking about it with each other. Looking back on it now, so many of their experiences were not consensual in any way.

As a young person, I had no idea what I was allowed to say “no” to. I felt like I had no agency over my body. I wonder how much of that has to do with feelings of being trans at a young age and feeling that disconnect.

I didn’t come out until my senior year. I came out as bi, but I knew that I was queer in a lot of ways. Gender wise, I didn’t start medically transitioning until three years ago, so well into my twenties. In high school, I had a suspicion of what was going on for me when I saw a trans person on TV for the first time in my life and I was like, “What? This is a thing that people do?”

I moved to Seattle after high school and sort of fell into this community of queer people of color that were all social workers or activists or community organizers in some kind of way. They had this very different lens of talking about how people interact with each other and that included a lot about sex, too, and relationships. That’s when I really started to explore what kind of relationship I wanted and how I wanted to show up to those kinds of relationships with other people.

It happened so much later in life than I would have liked, but I’m glad that it happened at all. I feel like for a lot of people it doesn’t.

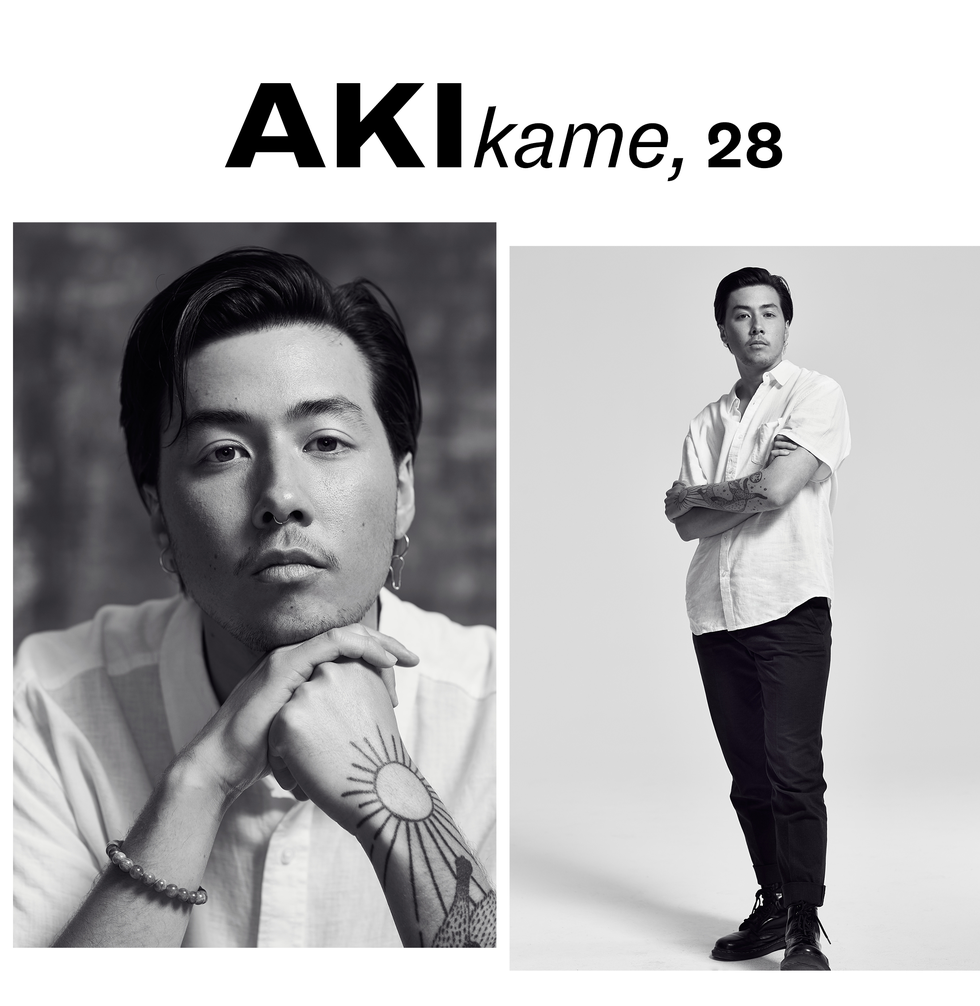

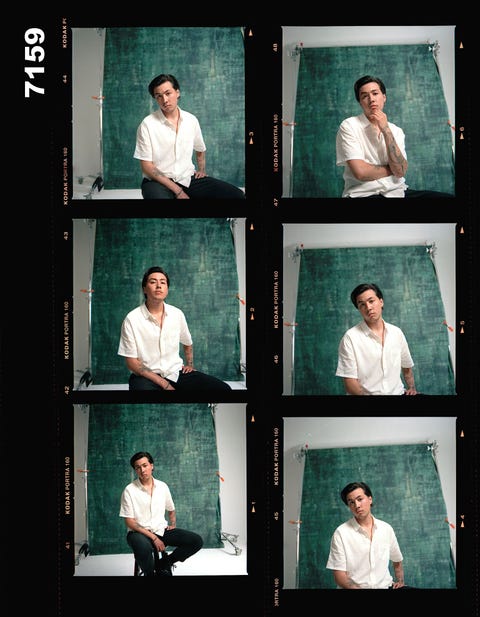

Aki Kame is a queer and trans photographer based in New York, originally from the West Coast and Japan. Their work is a manifestation of the love they feel for their community and part of a rich legacy of storytelling they want to carry on for LGBTQ generations ahead.

I had my first sex ed class when I was 18 and in the 12th grade. By that time, there was nothing you could necessarily tell me about my body and sex that I didn’t already know.

I grew up in Detroit, and my mom was a single mother raising two Black boys. I was molested at the age of eight, [and it lasted] until I was around 12 years old. I was introduced to the world in a pretty different way.

In sex ed, no one [talked] about sex in the context of queerness. You better believe Michigan is not mandated to have sexual education, and even then, parents have the option to opt out of their children being taught. But then at home, all they say is: “Don’t bring home no babies.”

Surprisingly, no one ever talked about HIV or AIDS growing up. I would vaguely hear about it at the gay clubs. I don’t even know if I knew what condoms were [when I was a teenager]. I remember thinking they were only used to avoid having babies, but not necessarily understanding that they were protecting me in the same vein.

I always say that I was the first person I met who knowingly and openly had HIV. I just assumed it was a disease for white gay men, because no one that I knew who looked like me had it. It was something you saw on Queer As Folk.

I was diagnosed when I was 21. I had been sexually assaulted when I was 18, and the next week I was deathly sick for four or five days. They couldn’t figure out what was wrong with me. They ran all the tests, but at the time it wasn’t protocol for the ER to give an HIV test when you came for an emergency.

Later, after the tests came back positive, I was unresponsive. I just sat there because I felt it. You just sort of know. I don’t know what that feeling is, but I just knew I had it.

Now, my main focus is helping young queer black boys go to school and receive higher education—whatever that looks like for them—but also being a sort of intermediary agent for them to connect them to resources that they need. Screenings, all of those things their moms don’t necessarily know about because they’re not black queer men.

Guy Anthony is an HIV/AIDS activist, artist, community leader, author, and the founder of Black, Gifted & Whole. He has dedicated his adult life to the pursuit of neutralizing local and global HIV/AIDS-related stigmatization.

I grew up in a town called Victorville, California, which is about an hour and fifteen minutes outside of Los Angeles. My parents were very, very adamant about my sister and I being in church. I signed two purity contracts when I was around nine and thirteen. It was co-signed by my dad, the notion being that he was the holder of my purity. I was making this agreement to the church, to God, and to my father that I was going to be pure by the time that I got married.

I was home-schooled for about half of my time in school. My mom and dad both gave me “the talk” when I was around seven. It was very much within the alignment of sex is between one man and one woman, and they are married and that’s the only way that sex comes into the picture.

I went to a very small, private-ish, charter-ish junior high school. I remember learning about anatomy in health class—“this is what a vagina is, here are the reproductive organs”— but it wasn’t quite sex education. It was very brief, maybe one or two classes. Those photos of a body being cut in half and being able to see where the uterus and cervix are—that was extent of it.

No one was talking about what consent was. It wasn’t until my ex-boyfriend and I broke up that I realized our entire sexual relationship wasn’t consensual, and there were actually many, many times where I was actually being coerced and assaulted by him. I had no idea, because the only education that I got about sex was, you know, you do it with someone you love. We said that we loved each other, and I assumed that’s all that you needed.

I identify as queer. I came out way later in life, and the reason why is because queerness was not on my radar. I was so indoctrinated into the church and I was fed the lies that being gay is a sin that I didn’t even know that I had access to that part of my sexuality. I was watching my friends experiment with their sexuality, but it just wasn’t even on my radar to think about myself being attracted to people beyond cis heterosexual men. It wasn’t until I was 17 or 18 that I started to realize: Oh yeah, I don’t think that I’m straight.

I respect my parents for wanting to keep me abstinent, and I know they were doing that as their way to keep me safe and protected. But I wish that there had been just a little more room for them to say: If you do have sex, here’s how to keep yourself safe, here’s where you need to go buy condoms, here are the things you need to be talking about when it comes to consent.

I really wish someone would have sat down and talked to me about what healthy sexual dynamics look like and the way that I need to speak up for myself within those sexual contexts.

When my husband and I first got together, I was processing a lot about religion and being by myself for the first time. Our relationship became a safe space for us both to go through this really grueling and hard and beautiful process of becoming sovereign and autonomous beings. Within that experience of being in this relationship I realized so many things. We were talking about exploring how my sexual trauma had affected the sex life that I was in currently. There was so much sexual growth—growth in general, but particularly sexual growth within our relationship. I feel so grateful that he was very, very patient with me as I was finding my way.

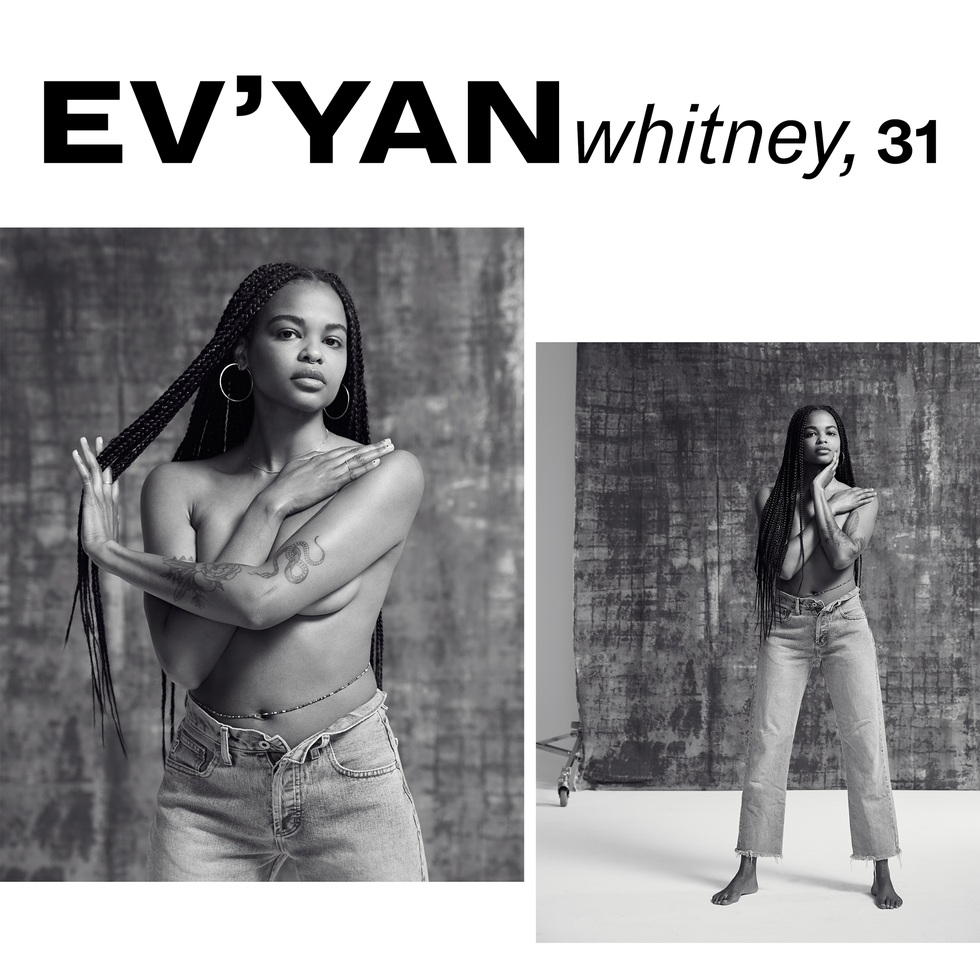

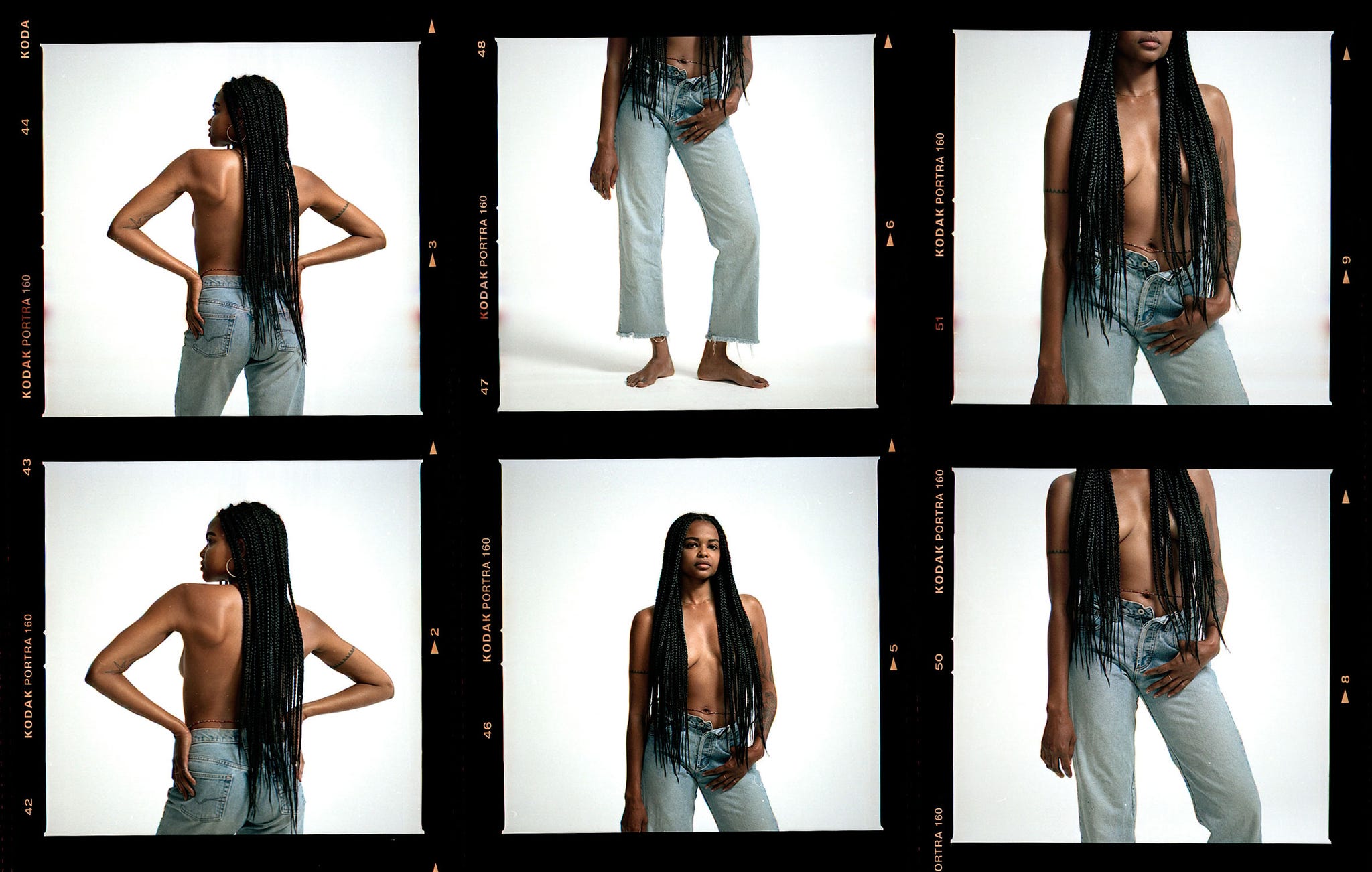

Ev’Yan is a sex educator, sex activist, and sexuality doula™ who works with women and femme-identifying people who want to step out of sexual shame and into erotic empowerment. She's also the host of The Sexually Liberated Woman podcast.

Both of my parents were in the military, so before I graduated high school, I moved about every year. The first time I can recall taking sexual education was in fifth grade in Norfolk, Virginia. I went to a school called The Stuart Gifted Center; it was a little Montessori-ish but more progressive.

I remember our sex ed program because they didn’t just have diagrams of a penis and a vagina; they also had LGBTQ sex education. They actually talked about same-sex couples. They didn’t push abstinence, and they talked about contraception. They talked about having a choice and women’s autonomy. HIV/AIDS was definitely mentioned, as one of the consequences of having unprotected sex.

I didn’t really have any sort of rigid gender roles growing up, and that’s been my whole reality until I joined the military when I was 17, as a quote-unquote female-appearing person. I grew up spending summers with my great grandmother, who’s indigenous. We don’t have regulations about what kind of sex people have, and we sure as hell never had regulations about monogamy. We're not gendered. A lot of people want to use the term non-binary, but for indigenous people, we don’t use the term because that’s still a Western ethnocentric lens.

In my culture, it’s a blessing to be Two-Spirit. Being Two-Spirit is beyond the frame of sexual orientation and gender. It’s literally the capacity to fulfill this ability to respond to your people.

One thing that would be really awesome to acknowledge in sex ed is the fact that queer people have existed for all of time. I think our conversations are always devoid of the spiritual element of the queer community; giving examples of the roles we fulfill within our family could be really intertwined in our education.

Queer people move in this space between the system. We are the completion of a circle that is masculine and feminine. That’s the way I wish sex ed was—that they actually talk about that. It changes the whole reality for our youth, even for the straight people in the room.

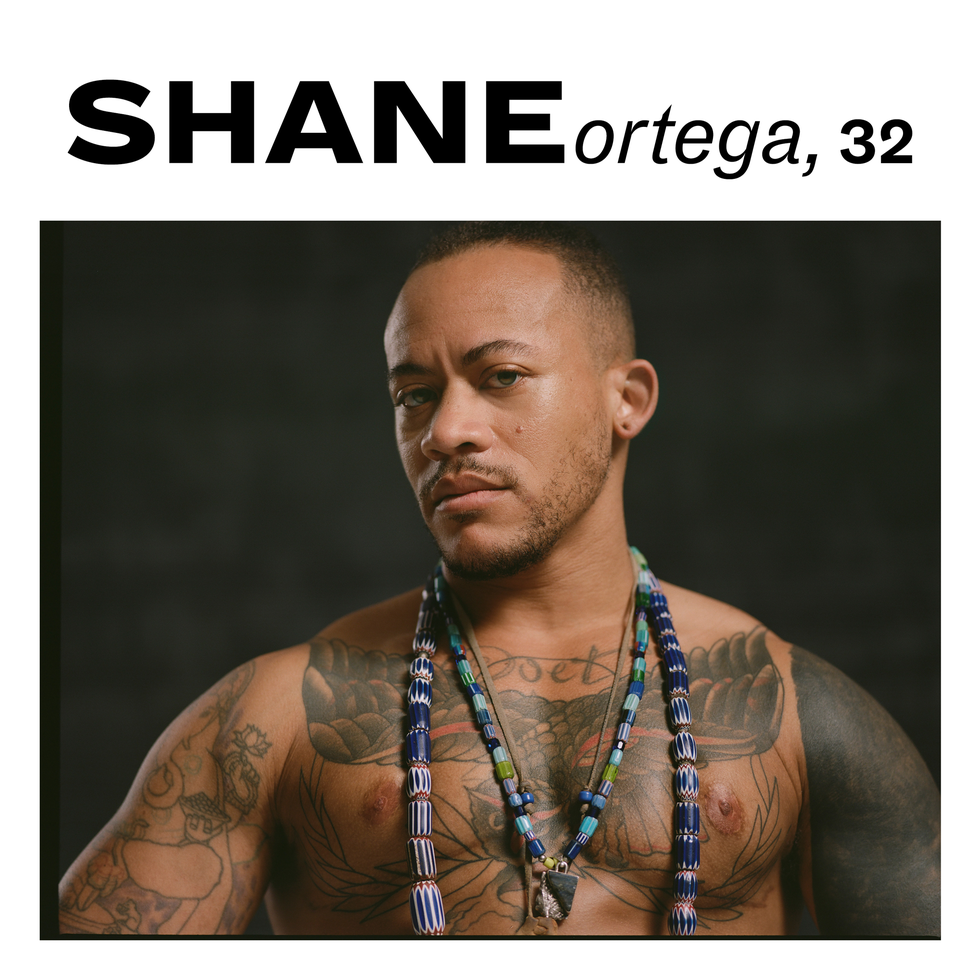

Shane is a retired Two-Spirit veteran of Tuscarora and Cherokee descent and an advocate for LGBTQ rights. He has dedicated his life to restoring balance in the world by integrating traditional and decolonized knowledge in dominant societal methods.

I grew up in Miami in a very Colombian and Catholic household. In sixth or so grade, my parents took me out of sex ed, which isn’t something parents should be allowed to do. Without that education, your kid could cause a lot of damage to the rest of the world. Everyone should be taught how to have responsible sex. I’m pretty sure I was the only one in my class who wasn’t allowed to take it. None of my sisters took it either. There were a few reasons why everything that happened to me happened.

I was a really late bloomer; I didn’t go through puberty until I was 15 or 16, and I was really naive to it all. I didn’t know anything. I had a lot of questions and I remember seeking information on the internet.

There was a lot of misinformation out there, for sure. I remember going to chat rooms dedicated to puberty and sex and when people would ask, “I’m confused about my sexuality” the response was: “It’s just a phase.”

In eighth grade, I remember my teacher briefly mentioning AIDS; that it was a terrible thing affecting gay men because they were sinning. Once I found out that you don’t just get AIDS for being gay, I thought it was only people who were being crazy-promiscuous got it. It wasn’t a thought in my head at all. I didn’t think that it would happen to people that didn’t sleep around, so I didn’t think I needed a condom.

When I found out, I asked how long I had to live. [At the time,] I thought I would be able to physically tell what someone with HIV looks like. I don’t know what that image was in my head, but it was not a normal person. That stigma is more dangerous than the disease.

I just want to remind everybody how lucky we are to be gay in 2019, and that a lot of people paved the way for us and we should really honor and really respect them and fucking run with that torch lit.

We need to get this thing out here and we need to educate and the only way we’re going to do that is with visibility. People need to see what HIV looks like, and until that happens, nothing is ever going to change.

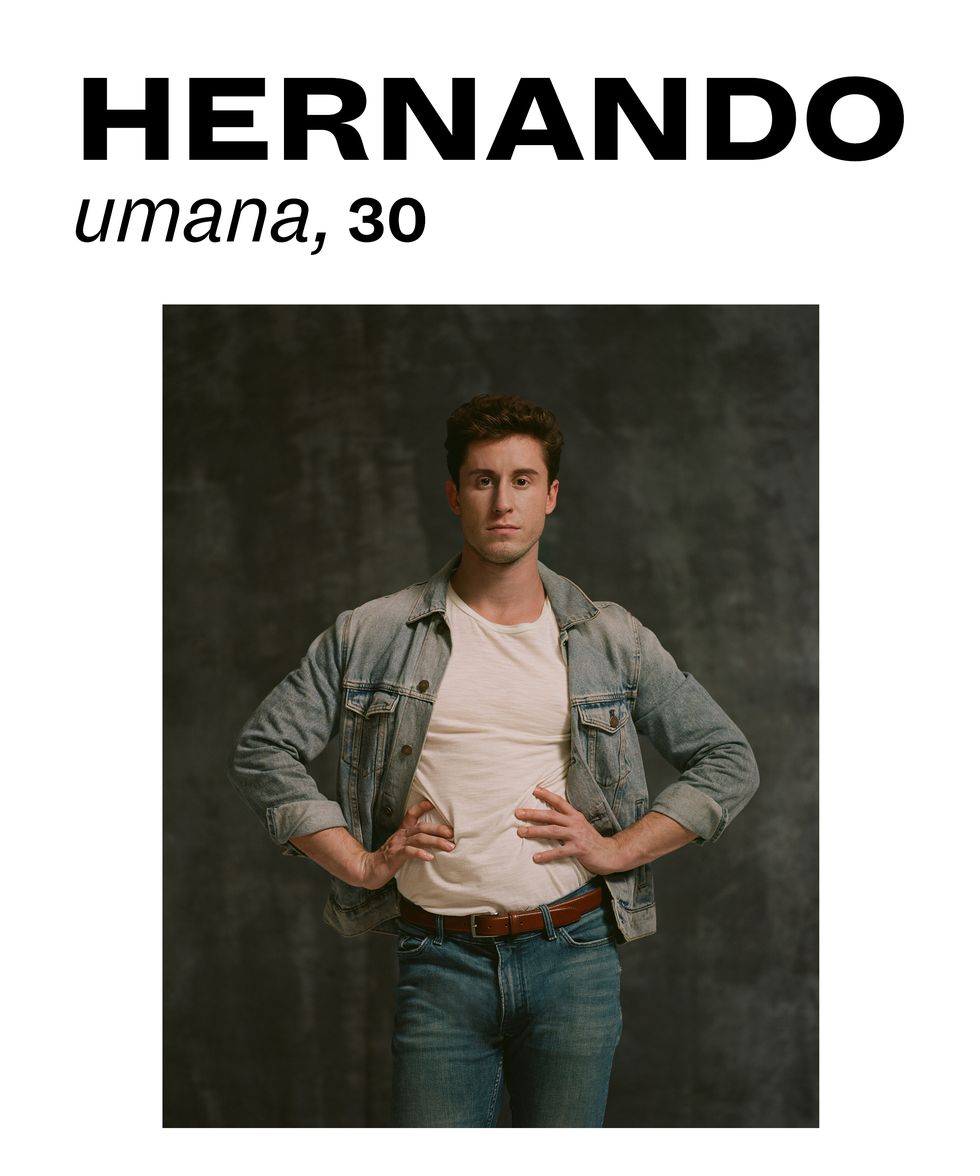

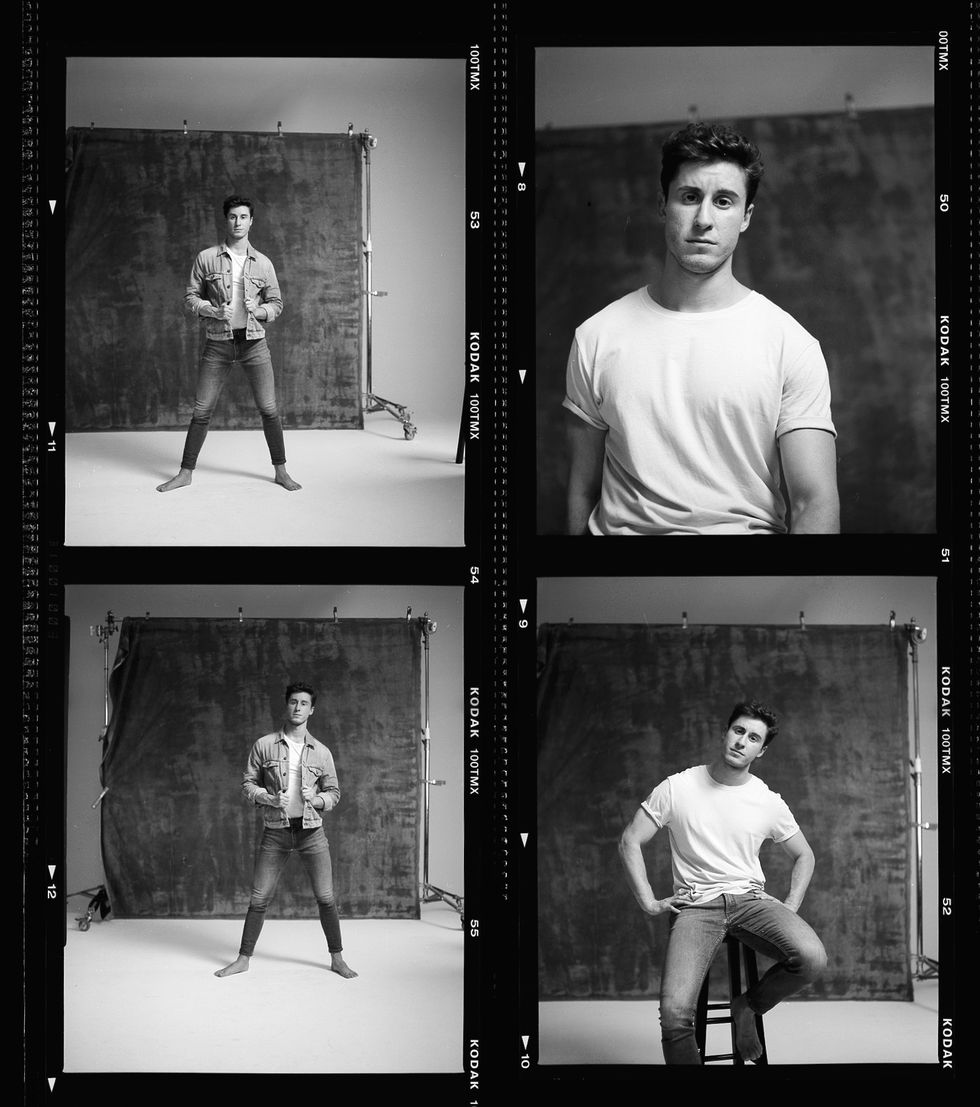

Hernando has performed on Broadway and is a proud, queer HIV activist and cannabis entrepreneur. He recently started a premium, full spectrum CBD for pets company called CBD Dog Health.