When Pita Taufatofua began the walk towards the stadium at the 2016 Rio Olympics opening ceremony, he was an unknown, unrated athlete from an obscure Pacific island. He would walk back out a global celebrity. Had it not been for a vat of coconut oil and his flair for flag bearing, he could have passed through the Olympic Games unnoticed and unreported.

As it was he went rogue, flagrantly disobeying officials who said “please just wear the suit”, hid a ta’ovala (Tongan mat which is wrapped around the waist) in his backback, nipped out the back and put it on just before the show got started, covered himself in oil, and by the time he had passed the thousands of people lining the streets on the way to the stadium he was going viral. When he stepped into the lights of the stadium waving his flag, articles were already being written about the distractingly shiny Tongan flag bearer and Twitter was melting down. “The internet came to a grinding halt,” reported Entertainment Tonight.

Afterwards, when he was standing on the bus “in my oil”, things “just went crazy”, he recalls. “You look at your phone and you can’t keep up with it.”

He was, he says, completely unprepared. There was no management, no sponsors, no money, no products, just him and his coach, Paul Sitapa. “It was the first time I heard about what a manager is, what a publicist is, what an agent is. It was just me and my coach trying to manage all this. Two people who didn’t know anything. No one had ever heard of Tonga. We were like, how is this even possible?”

Taufatofua says he was just trying to represent his country by wearing its traditional costume. “I was representing 1,000 years of history. We didn’t have suits and ties when we traversed the Pacific Ocean.”

If he is being disingenuous (his ancestors probably weren’t oiled up), if he was seeking attention, he got it. He now had the eyes of the world on him for his taekwondo tournament which was right at the end of the Games. “I had to try to stay focused. That was very hard. Now there was more pressure because everyone was watching. They wanted this guy out of nowhere who had this moment to win gold.”

He was knocked out in the first round – 16-1 to the Iranian Sajjad Mardani – but it didn’t really matter because he had already won.

By the end of the week there would be 230 million Google searches for “where is Tonga?”

“Those were the stats that were given to us by Google trends,” he says.

There would be appearances on US talk shows as he became a darling of the American media.

And there would be a run at the 2018 Korean winter Olympics in another sport – cross-country skiing. He had barely even seen snow when he announced this, and it involves an even more dramatic story than the taekwondo tilt. But we will get to that.

‘Everything was going wrong’

We meet in Suva where Taufatofua is on duty as the Unicef Pacific ambassador. He has just spent a day with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex in Tonga and is here to appear on the reality TV show Pacific Island Food Revolution, which is being filmed at the Grand Pacific hotel. Taufatofua wishes the Unicef budget stretched to this luxurious hotel, but unfortunately it doesn’t.

In person, Taufatofua, 34, is very far from his shirtless beefcake image. He is polite, well-spoken, an educated man with a degree in engineering from the University of Queensland, and a Christian who worked with homeless kids for 15 years at Brisbane Youth Service. The perfect teeth are fairly shiny and the now-famous torso is encased in a blue Unicef T-shirt. But man, does he have a story to tell. He had already won simply by getting to the Olympics. There was no overnight sensation about that. It had taken 15 years and a world of pain. “From memory, six broken bones, three torn ligaments, one-and-a-half years on crutches, three months in a wheelchair and just hundreds and hundreds of hours of physiotherapy,” he says.

While he is humble, there is no mistaking the strength and self-belief that Taufatofua carries. That and the extraordinary perseverance comes, he says, from “getting my arse kicked for years, it gave me a whole lot of strength. Everything negative in my life has been fuel for me.” Tenacity comes, he says, “from not having anything as a kid”.

His mother, who is Australian, was a nurse and is now a sanitation consultant in the South Pacific; his Tongan father has a PhD in agricultural science and worked in government research. He was born in Brisbane but went to school in Tonga. There were seven children and not much money; a one-bedroom house, scarce electricity and no hot water. “They had no money because they paid for us to have the best education. Between us there are eight degrees and two masters.”

In Tonga he was seen as physically smaller than anyone else. He was benched for the entire four years he played football, even though “I never missed a training session. I trained every day,” he says, The only time he got on to the field was to give the other footballers oranges and water. “The coaches never believed in me. In my head I was the little dog that barked and no one saw the little dog.”

When he was five his mother put him into taekwondo for “self-defence, to look after myself. My whole family did it. My brother got his black belt”.

When he was 12 the streets from the airport to town were lined with people cheering Paea Wolfgramm, the first Tongan to win an Olympic medal, a silver in boxing at Atlanta in 1996.

“That was when I thought ‘I am going to the Olympics’. And it just never left,” Taufatofua recalls. “I was working full-time, studying full-time, I was training full-time. It was always ‘you will be an Olympian’. It is quite an interesting thing.”

And so began the years of pain and crushing disappointment.

Every four years there is one shot at the Olympics with a qualifying tournament. “I have to be number one in Oceania to qualify for Tonga.”

In 2008 he went to the qualifier in New Caledonia and left in a wheelchair.

He had been up one point when he sprained an ankle and fractured a bone in his foot, but kept fighting another two rounds until it burst. He was unable to walk for six months.

There are no elite sports institutes for Tongan athletes, no vast reserves of government funds for Olympic dreams.

In the darkest days he would draw on the homeless kids he worked with. “I saw just what true strength was. We had kids who had been abused in every way possible but were brave enough to get good outcomes. It was just a competition, I didn’t have the right not to believe in myself.”

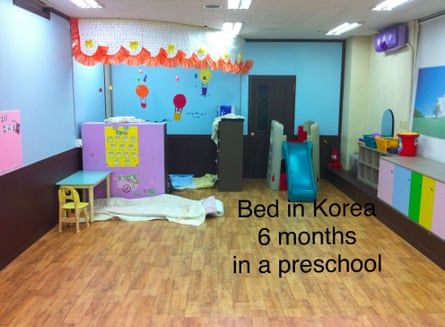

In 2011, getting ready for the London Olympics, he went to train with the taekwondo masters in South Korea, desperately short of funds. “We slept in a preschool for six months. We slept underneath the desk. Because it was a preschool for church they let us sleep there but in the morning we had to pack up our bags before the kids came in and then go out for the day. We had no money. It was as uncomfortable as anything.”

At the world championship in Azerbaijan, which was an Olympic qualifier, he tore a knee ligament, normally a six-month injury. Eight weeks later, not wanting to wait another four years, he made it through to Oceania Olympic qualifier, fighting on one leg. “We wrapped it as thick as we could. I changed my stance. I fought all the way through to the final. Then I fought against a guy from Samoa who had beaten me before. I was beating him and then in the last round his coach had seen that I was only using one leg and he got up on me and beat me.” This time Taufatofua left New Caledonia on crutches, unable to walk for another three months, while the Samoan went to the Olympics.

He kept competing across the Pacific, winning and losing, injury after injury. Surely people were telling him to stop punishing himself. “Doctors, lots of people, told me not to go on. It is really hard to describe just how clear it was in my mind that I will become an Olympian. There was a confidence there that I didn’t create, I believe it was God-given. I can’t explain it other than I just knew it would happen.”

And so to 2016 and Rio. “Everything was going wrong. I was running out of money, my car was breaking down, my relationship was breaking down. Paul calls up and says the [qualifying] competition is in two days we have to get to Papua New Guinea. I am ready but I have no money. Paul called up a lady he knew in Tonga and she funded my first ticket ever. We got there the day before the competition.”

Up against a New Zealander who had consistently beaten him, the score was three all at the end of three rounds and went into golden points; the first to get a point wins and becomes an Olympian. And he kicked at exactly the right time. “That was my moment. It was the most emotional time. Rio, oil, that wasn’t my moment – that was the reward for all the work.”

Four months before the Olympics he was broke. He and Paul did fundraisers and rented a house in Brisbane. They trained in the garage to save money, yelling a lot. “I had my coach, we had prayer, I was happy, I had qualified, I was going,” he says.

‘I chose to learn from the failure’

Perhaps it was all the attention, perhaps that kind of energy is addictive, but a few months after Rio he announced that he would attempt the Winter Olympics at Pyeongchang as a cross-country skier. As a person who had spent his entire life in the tropics, this seemed hilariously bonkers, up there with the Jamaican bobsledders. “I chose it because it made no sense,” he chuckles. “I love these challenges.”

He watched YouTube videos of professional races and at 5am every morning he would put on rollerskis and train in the park. “The amount of concrete I ate. But I had one year to qualify,” he says. But then he had to qualify on actual snow. And it got real – on rented skis. “We had to get to all these countries to try and get the races. I think it was 15 countries in eight weeks. The problem was we had to go to races which were not the hardest races where the world cup winners would be, it would be too hard. At this stage every single athlete from every country was getting ready for the Olympics. I came last in four out of nine races.”

He would run up $40,000 in credit card debt.

By then he had buddied up with Chilean Yonathan Jesús Fernández and Mexican German Madrazo, whose prospects were as farcically bad as his were.

None of the ski companies wanted Taufatofua to be seen on their skis. “I was asking for a good price and they looked at me and said ‘I suggest you wear other skis’. That happened through the whole qualification process, to me and my friends from South America.”

In Poland a ski fell off and went flying down a hill and into trees. “I had to go down a hill I had already climbed up, spend 20 minutes looking for it, fix and tape it back on. They were shutting off the lights when I came in,” he recalls.

He wasn’t even close to a qualifying time and he was running out of races.

“I get across to Armenia. I thought it would be the last race. Two or three thousand metres up. Normally you go there two weeks before to acclimatise. We got there the day before. I got destroyed in the race again. I was devastated. There wasn’t any more time left to qualify.”

They found out there was a race in Croatia the next day. But it would be almost impossible to get there in time.

“We looked at every country around Armenia to get a flight. Every country around Croatia. I then end up in an eight-hour taxi ride through Armenia, through the Georgia border, with no sleep. I called the race officials and said I was coming in late. They said they could put me in at the end of the race and then I would start last. I fly across to Istanbul to get a flight to Croatia, and missed the gate by five minutes. I am there pressing all the buttons in the airport, maybe I was a bit crazy by that time. And it didn’t work. I am stuck in Turkey with no money and no flight out of there. I have missed the race in Croatia.”

His brother, who is a lawyer, used his points to get him on a flight to London, where he lives.

With four days left in the Olympic qualification period, they found out there was one more race – in Iceland on a fjord in the Arctic Circle. The three amigos bought one-way tickets to Reykjavik, Fernández and Madrozo flying from Armenia and Taufatofua going courtesy of his brother’s air miles.

“We land, snowstorm. There is no flight from Reykjavik to Eskifjörður fjord. So we rented a car. Normally a 10-hour drive. But because of the snowstorm it took us three days,” he says.

Then they heard that three avalanches had blocked the road. “I said, ‘Guys we are going to drive as far as we can and park the car and then hike.’ But by the time we got there they had cleared it, just.” Taufatofua went to the hotel and prayed. Tomorrow was going to be the last day to qualify. He only had one set of skis. “Norway has 40 pairs each. They have a $5m budget just for the waxing. If the conditions were hot or cold, dry or wet, you use a different ski. It just so happened that for what I had it was the perfect day. It was the one race I had where I felt the ski was the right ski. I did the race and qualified with five minutes to spare. And that is how I made my second Olympics.”

Naturally he did the oiled shirtless thing at the opening ceremony, even though he risked hypothermia. This time there were no officials to stop him, he was the only athlete from Tonga. And by now the fame was not so accidental. “My goal was never to be famous because with it comes responsibilities. But what you can do with fame is another thing,” Taufatofua says.

There was no question of a medal at these Olympics – “No way, not in that sport.” His main goal, he told the media, was “Finish before they turn the lights off. That’s number one. Don’t ski into a tree. That’s number two.”

He didn’t even come last. He came in just under 23 minutes behind the gold medal winner Dario Cologna from Switzerland and waited at the finish line for his friends.

Today there is something slightly messianic about Pita Taufatofua. “I always chose to learn from the pain and the failure,” he explains. “It is not special to me, it is something that is transferable to anyone if they have the right mindset. The alternative is to sit down and do nothing with your life and to always feel that there is something else that you should be doing. Everyone has potential. It is whether you act on it or not act on it.”

He might never have won an Olympic medal, but Taufatofua has seized the constantly astonishing day. There is management, film and TV offers. He has given a speech at the United Nations general assembly and another at Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Justin Trudeau. He has written a motivation book, The Motivation Station, and another one on depression.

“I have my faith and I believe my purpose is bigger than myself. If I am meant to help a million people have confidence, I don’t have the right to be depressed.” Taufatofua says he is too busy to be in a relationship: “I want to make sure that everything I give has to be the best. And I can’t give a relationship the best because I am moving around.”

Now a serial Olympian, in late February he will announce his third attempt at an Olympic sport. It will be a water sport this time, but for the moment it is top secret. Watch this space.