CHANGE Report on Arts and Culture and the Revival of the Hawaiian Language

Part 1: State of the Arts

The Arts express our shared humanity but struggle to expand their audiences

uring the opening night of the Honolulu Biennial 2019, more than 2,000 people walked around the former Famous Footwear space at Ward Centre, immersing themselves in sculptures, woven garments, drawings, videos and an intricate, abstract network of red yarn.

“I think it told us there’s great interest in contemporary art,” says Katherine Ann Leilani Tuider, executive director and co-founder of the Honolulu Biennial Foundation. “When we were building the biennial, we got feedback that people wouldn’t necessarily be interested in the type of work we wanted to show, (but) I think the 2017 biennial, and echoed again … this year, shows there’s tremendous interest in what is contemporary art for our local community.”

John Koga, a contemporary artist in Honolulu and co-chair of the Hawaiʻi CHANGE Initiative’s Arts and Culture Committee, says arts and culture in Hawaiʻi is alive and moving forward. There are many activities, he says, that provide access to different areas of the arts, like the Honolulu Biennial and iBiennale that took place in the spring, and the Hawaii Youth Symphony and Hawaii Youth Opera Chorus that engage keiki in music.

What needs to improve, he and others say, is people’s participation in the arts, whether it’s as artists, patrons or supporters. “I just think it needs to be more of a constant,” he says, “and I don’t think everything needs to be a blowout or knockout thing. It just needs to be part of our daily culture in a sense. I liken things to eating, to food. It’s just part of the daily routine.”

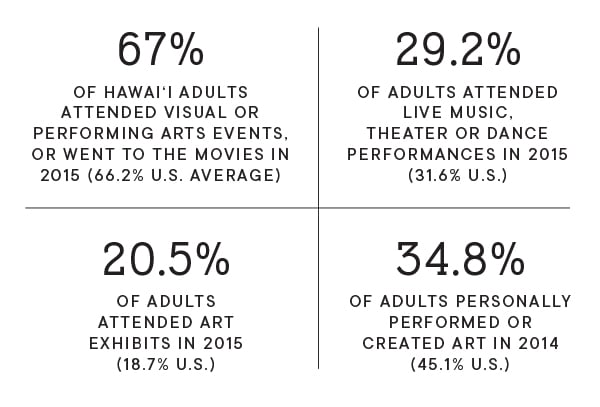

PARTICIPATION IN THE ARTS

Source: National Endowment for the Arts, State Level Estimates of Arts Participation Patterns (2012-2015)

Terence Liu, CEO of the Hawaiʻi Arts Alliance, says building an audience to see the arts is a challenge across the country, and it’s not necessarily about the cost of tickets.

“People don’t give themselves a chance to go and hear what it sounds like when the whole symphony orchestra is on stage and you’re in the hall and you’re hearing that that is a sound. That affected me when I was a kid because my parents took me in there (to the Cleveland Orchestra),” he says. “And I heard that sound and it was life-changing when I was a little boy.”

He adds: “If artists are on stage and they’re doing something, and nobody is out there, it’s like it didn’t happen. Art requires audience. It’s part of what art is.”

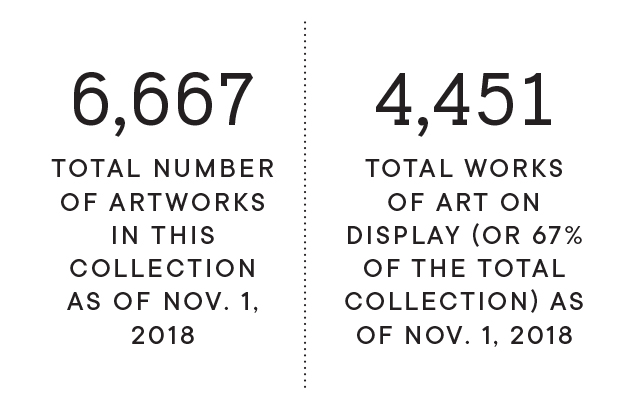

Engagement with the arts is a key focus of the Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, the state agency dedicated to promoting and perpetuating culture and the arts. The foundation administers the Art in Public Places Program, which places purchased, donated and commissioned artwork in state buildings and other public spaces. More than 6,500 artworks are in this collection.

“It’s not so much that we place the art – because we did that for many years – but now how do people respond to that, how do they engage in that, how does that become part of their life,” says Jonathan Johnson, executive director of the foundation. Now, he adds, the focus is: “What do the arts do for me?”

High Value

Arts and culture are at the core of a people’s well-being, says Georja Skinner, chief officer of the Creative Industries Division in the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism.

“It takes you to a place that’s more indescribable, but you feel it,” she says. “Just like people hear Hawaiian chant, they don’t know exactly what the people are saying, but it moves them to tears. Why? Because it touches that part of us that is the essence of life.”

Donna Blanchard, managing director of Kumu Kahua Theatre and consulting director of The Arts at Marks Garage, says arts are the only way to recognize people’s shared humanity: “When you see a play or a painting or hear a song that moves you, you’re experiencing something that is more of you. It makes you more you. You can read books on your own and you can listen to music on your own, but when you share that in a community setting, it multiplies the effect.”

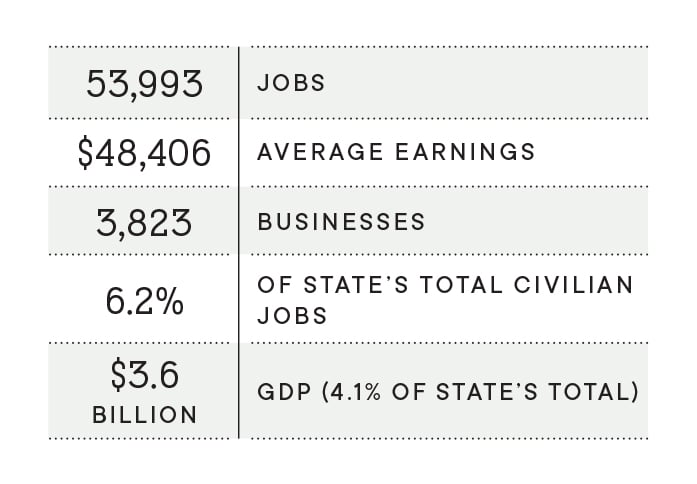

Skinner says Hawaiʻi’s creative economy is thriving. Her division advocates for Hawaiʻi’s culture, arts, music, film, publishing, digital and new media industries; according to its March 2019 report, the Islands’ creative industries accounted for 53,993 jobs and 3,823 businesses in 2017.

Bernice Akamine’s “Kalo” installation at Ali‘iōlani Hale during the 2019 Honolulu Biennial. | Photo: Courtesy of Teri Skillman

“That speaks to the vibrancy of both the for-profit and nonprofit sectors because both of them are the fabric of any creative economy in any region,” she says, adding that Hawaiʻi’s position in the Pacific gives it the opportunity to export its creative goods, like fashion and Hawaiian music and hula. (Read Hawaii Business Magazine’s coverage on Japan’s love of Hawaiian music and hula.)

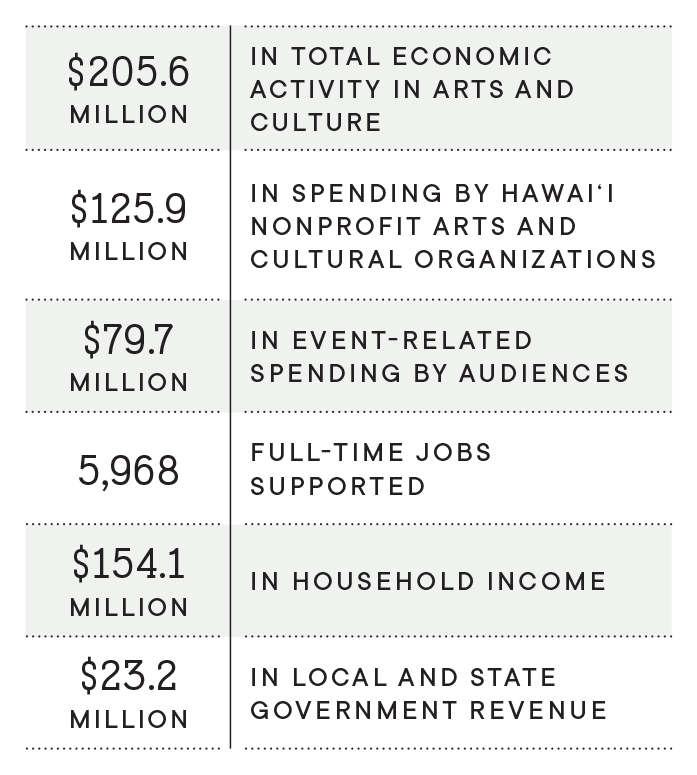

A 2017 report by Americans for the Arts found the Islands’ nonprofit arts and culture sector generates $205.6 million in economic activity. The study looked at the spending of 109 local nonprofit arts and culture organizations and the event-related spending of their audiences. Audience spending totaled $79.7 million, with each attendee spending an average of $25.26 for things like meals, transportation and clothing.

When people ask Tuider how to justify spending money on the arts, she tells them the arts are an economic powerhouse that can help diversify the state’s tourism-dependent economy.

“It’s not like just butter on the bread. … It is the yeast. It is the very thing that gets it all going. It gets people rallied against issues, it creates jobs, it stimulates our economy and it also creates peace and joy. It improves the overall well-being of our community,” she says.

ECONOMIC IMPACT

Arts and culture impacts the Islands’ economy. Here are two studies that provide different numbers: Arts and Economic Prosperity 5, which looks solely at spending by Hawai‘i’s nonprofit arts and culture organizations and their audiences, and a report by the state Creative Industries Division, which looks at the jobs and businesses that are part of Hawai‘i’s culture, arts, music, film, publishing, digital and new media industries. As with many economic impact studies, the information in these reports should be taken with a grain of salt.

Arts and culture impacts the Islands’ economy. Here are two studies that provide different numbers: Arts and Economic Prosperity 5, which looks solely at spending by Hawai‘i’s nonprofit arts and culture organizations and their audiences, and a report by the state Creative Industries Division, which looks at the jobs and businesses that are part of Hawai‘i’s culture, arts, music, film, publishing, digital and new media industries. As with many economic impact studies, the information in these reports should be taken with a grain of salt.

Arts and Economic Prosperity 5 is an economic impact study by Americans for the Arts, an organization dedicated to advancing the arts in America. Numbers were collected from fiscal year 2015.

The Creative Industries Division study was published in 2019 and looks at metrics from 2017. The CID is housed in the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism and acts as a business advocate for Hawai‘i’s creative industries. According to the report, “CID/DBEDT is positioning the state to be a national and global leader in creative sector development as well as a hub for creative media and film development in the Pacific.”

Maintaining Relevancy

Public support is vital to the survival of a vibrant arts and culture community. As existing patrons and donors age, arts and culture organizations are shifting to attract younger supporters while remaining relevant for existing audiences.

“Everybody targets the younger crowd,” says Joyce Okano, president of the Friends of the Hawaiʻi State Art Museum. That can mean using technology, but as Johnson of the Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts says, technology can be double-edged. The Hawaiʻi State Art Museum, for example, uses social media to bring in specific audiences for different events. On the other hand, people could stay home and scroll Instagram instead of learning how to play the ʻukulele every Wednesday night, he says.

Kahilu Theatre’s demographic is typically 60 and older. But Deborah Goodwin, executive director, says the theater in Waimea on Hawaiʻi Island is “energetically striving” to bring in the next generations. She says one challenge is that Hawaiʻi’s high cost of living can make it daunting for some people to see a performance, so the theater offers opportunities to see some shows at lower prices. And it has broadened its appeal with promotions such as dance nights.

“With bands including Big Island favorites Lucky Tongue, Lorenzo’s Army, and Streetlight Cadence, the program attracts a younger crowd, important in our mission to diversify our audience and patron base, to mix, mingle and dance on stage,” she says, adding that the theater’s galleries are also open for guests to enjoy.

The Hawaiʻi State Art Museum has also changed its First Friday offerings to include alcoholic drinks, valet parking, music, fashion shows and lectures to increase the attendance of Millennials, Okano says.

Art Vento, president and CEO of the Maui Arts and Cultural Center, says arts centers need to figure out how to be relevant for a new generation: “We need to figure out how it is that they feel connected to this place. Is it through free events? Is it through new art forms that are happening? Is there programming for kids and the grandkid? For the Millennials, is there an opportunity to see electronic dance music here?”

Older people may not like those things, he says, but if they return to the center another day, there’ll be different events that might appeal to them. The key, he adds, is to have diverse experiences and tickets available in many ways, such as at the box office and online.

“Our job is to make everybody feel good about their choices,” he says. “We have to survive, we have to figure out a way to pay the bills today, which is no small feat, but we also need to figure out how we’re going to stay relevant for tomorrow.”

The Maui center puts on about 1,700 events a year and sends performers into Maui County schools, senior centers and social service agencies through its Artists in the Community program. Those interactions can be life-changing, he says.

“If that happens to one kid, or one person in rehab, or one person in a school, an auntie in a kupuna center felt alive and invigorated for that 45 minutes to an hour where somebody cared enough to make the time to do that, then we’re doing the things that can help a community feel good about what we’re doing,” Vento says. “And that’s contagious. We need to be contagious.”

The challenge for Adaptations Dance Theater on Maui is raising the low public awareness of contemporary dance theater, says Amelia Couture, co-founder and co-artistic director. It’s hard to describe what contemporary dance theater is because it encompasses many genres, including jazz, ballet and hip-hop. To really understand it, contemporary dance theater must be seen live, rather than on a screen, says Hallie Hunt, co-founder and co-artistic director.

“It is a performance art that is meant to be experienced live, when you can feel the power and heat radiating off the stage, see the sweat dripping from the physical exertion, hearing feet and bodies connecting with the floor or each other. This is why it is important to see it live so audience members bring their friends and family next time to share in the experience,” she says.

Koga, the contemporary artist, says more crossover between different art forms – as well as with other activities – will engage a broader audience. While many people support the arts by going to events and activities, it’s often the same group of people.

There are several efforts to encourage new people. Donnie Cervantes, director of Aupuni Space, a contemporary art gallery in Kakaʻako, says the Trades Artist in Residence program he co-founded is partly intended to make artists and ideas in contemporary art more accessible to more people. For instance, art focused on environmental issues might draw new people.

More Support Needed

Tuider says the Honolulu Biennial is trying to create a structure that supports local artists. The biennial’s foundation covers production costs for commissioned work as well as travel for artists to do research and attend opening night. This lets attendees meet the artists and discuss their processes – an interaction that may generate greater appreciation for artists’ work.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been approached by people asking for free art. You’d never ask a chef to work for free. You’d never ask a plumber to work for free. So why would you ask an artist to do their work for free?” Tuider asks.

Blanchard, of Kumu Kahua Theatre and The Arts at Marks Garage, thinks it’s easy to devalue what artists do because they will create art even if they don’t get paid.

“You need to recognize that artists need our support and for those people who are able to support, they should,” she says. “And for those people who cannot, they really need the others to step up so that they can still have art in their lives.”

Marques Hanalei Marzan, a fiber artist and cultural advisor at Bishop Museum, says appreciation of arts and culture has been lacking since he was a student at UH Mānoa in the early 2000s.

“Passage” by Mamoru Sato is part of the Art in public places collection and located on Punchbowl Street at Halekauwila in Honolulu. | Photo: David Croxford

“My experiences traveling the world and seeing different cultures and communities really appreciate and support the arts, it made me really look back and see how that environment isn’t here locally as well as nationally,” he says, adding that he’s tried to find ways to bring artists and practitioners into the museum to educate the community about different art forms and culture.

Melanie Ide, president and CEO of Bishop Museum, says it’s challenging to get more people to provide support because what arts and culture institutions provide can’t be quantified by numbers. She says the one way to imagine something’s value is to think about what happens if it didn’t exist. “I think it’s taken for granted that somehow it should be free and done freely. (But) it shouldn’t be at the burden of artists and cultural producers to function without support.”

She says state appropriations for the museum have dropped significantly – about 75 percent in the last 20 years. State support for the arts comes in waves, says state Sen. Brian Taniguchi, chair of the Senate Committee on Labor, Culture and the Arts. The arts are the first to lose funding during hard times, and even in good years, he admits, there’s not much support. One effort that has helped stabilize arts funding is Hawaiʻi’s law requiring 1% of construction costs for all new state buildings to be dedicated to acquiring art. The only downside, he says, is these funds can only be used for visual arts, not performing arts.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been approached by people asking for free art. You’d never ask a chef to work for free. You’d never ask a plumber to work for free. So why would you ask an artist to do their work for free?” – Katherine Ann Leilani Tuider, Executive director and co-founder, Honolulu Biennial Foundation

“Artists are going to do their art regardless if they get support because it’s their passion, but it’s not going to be as vibrant if we don’t have government and organizational support and patrons,” says Vicky Holt Takamine, executive director of the Pa‘i Foundation and kumu hula of Pua Aliʻi ʻIlima. “So it’ll survive but I think in order for our community to really thrive … we need some really forward thinking and out of the box opportunities.”

Koga hopes that American Savings Bank’s Loʻi Gallery will set a new standard for corporate support of the arts. The gallery in the bank’s new headquarters on the corner of Beretania and ʻAʻala streets features 1,464 linear feet of space dedicated to local art.

“This area was once filled with lush loʻi kalo (taro patches). Just as the loʻi nurtures the kalo, this gallery supports local artists, enabling them to share their talents with the community,” reads a message on one of the gallery’s walls.

The gallery features different artists every four months, and the community will be invited at the beginning of each rotation to see the art and meet the artists. Koga, who came up with the idea for the bank’s gallery, says what’s unique about this space is that featured artists are paid $500 to show their work – which he says is rare – and get to keep 80% of the proceeds from any sales. Beth Whitehead, executive VP and chief administrative officer at American Savings, says the remaining 20% of the proceeds are donated to nonprofits collectively chosen by the artists and bank.

ART IN PUBLIC PLACES

The Art in Public Places Program was created in 1967 and is funded by the Art in State Buildings Law, which designates 1% of the construction costs of new state buildings to be used to acquire art.

Objectives of the program include:

- Enhance the environmental quality of state buildings and public spaces

- Cultivate the public’s awareness and appreciation of visual arts

- Help develop and recognize a professional artistic community

- Acquire and display works of arts that are expressive of Hawai‘i and its people

Not Enough Venues

Several artists agree the Islands need more spaces for artists to create and showcase their work.

Artist Bernice Akamine says artists on Hawaiʻi Island need more collaborative art centers, serious art spaces to show contemporary art and open studio space. Couture, who helps run Adaptations Dance Theater on Maui, says good rehearsal and performance spaces are expensive to rent and Hawaiʻi should make it more affordable for local dance companies to perform. On Kauaʻi, spaces for art-making activities are limited and unaffordable, writes Carol Yotsuda, executive director of the Garden Island Arts Council, in an email.

Jonathan Johnson of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts says the need for space can drive innovation and bring the arts to new venues – thus increasing public accessibility. One example, he says, is the Kauaʻi Society of Artists gallery that’s located in the Kukui Grove Center in Līhuʻe.

Georja Skinner says musicians, artists and the film industry need a central space to collaborate with other artists and businesspeople. The state Creative Industries Division’s newest project is called Creative Space 808, which will function as coworking spaces with creative tools and studio space. The plan is to open two facilities in Kakaʻako this year, both run by third-party operators. Eventually, Skinner hopes to add more locations around the state.

Another effort is the Ola Ka ʻIlima Artspace Lofts, a mixed-use project in Kakaʻako for artists to live and work. Takamine says the idea for the project arose because many hālau don’t have their own dedicated space to practice.

The bottom level of Ola Ka ʻIlima will house the Pa‘i Arts and Culture Center, where Takamine’s hālau will move to from its current location in Kalihi. She plans to make the space available to other hālau and arts organizations. The upper floors will house 84 one-, two- and three-bedroom homes for renters making between 30% and 60% of the area’s median income. The building will also feature gallery and commercial space.

She says the mixed-use development will let artist residents collaborate and learn from one another. The lofts are expected to open this summer.

A Way Forward

Marzan, the fiber artist, remembers every moment of his first lau hala weaving experience. He was in high school and took a class at Bishop Museum, and “it just really opened up all the floodgates and made me go in every direction and really embrace that lau hala weaving and just beyond that, creativity and expression,” he says.

Today, he says, more opportunities are needed for younger generations to get involved in the arts. Many of the people interviewed for this story agree that arts education is important to ensuring continued support and appreciation for Hawaiʻi’s arts and culture communities.

“That is another indicator I think that perhaps organizations like mine are experiencing. If you aren’t exposed to the arts in schools, you will not have that affinity or that loyalty to it as you mature,” says Goodwin of Kahilu Theatre.

Meleanna Meyer, an artist educator, says there’s a need for more arts education in public school classrooms. The federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001’s emphasis on state testing meant that the focus of many schools was on what would be tested, rather than on the arts – and she says that’s still felt today.

Una Chan, the educational specialist who oversees visual and performing arts in the state’s Department of Education, says she’s seen public schools become more interested in arts education over the last three years she’s been in the position. Many times, she says, it’s because of the DOE’s emphasis on educating the whole child. The DOE has several partnerships with community arts organizations to bring arts education into the classroom and expose keiki to art.

Several sources agree the arts can do wonders for keiki. They say it can help them build the 21st century skills – such as problem solving, communication, critical thinking, creativity – that they’ll need as adults, broaden their perspectives, build greater self-confidence and learn that it’s OK to fail.

The arts, according to Kate Welch, arts integration curriculum coordinator at Pōmaikaʻi Elementary School, help engage students and encourage active learning. Pōmaikaʻi uses arts integration as a teaching approach, with students constructing and demonstrating their understanding through art. That process involves a lot of collaboration, reflection and revision.

The skills that students pick up in arts education are “keys to problem solving that our society needs,” says Johnson of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, which has several arts education programs, “and making sure that we put those into the schools will help raise a group of people who can actually work together and solve problems. Our goal is not that they become fine artists; it’s that they become contributing community members.”

Quicklinks

Part 1: State of the Arts

Part 2: “We’ve Really Moved the Needle”

Part 3: How You Can Help